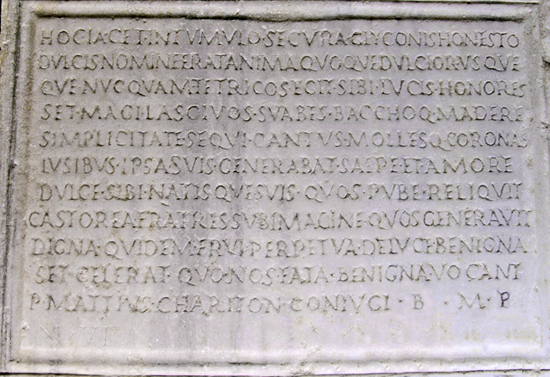

HOC IACET IN TVMVLO SECVRA GLYCONIS HONESTO

DVLCIS NOMINE ERAT ANIMA QVOQVE DVLCIOR VSQVE

QV[a]E NVCQVAM TETRICOS EGIT SIBI LVCIS HONORES

SET MAGI[s] LASCIVOS SVABES BACCHOQ[ue] MADERE

SIMPLICITATE SEQVI CANTVS MOLLESQ[ue] CORONAS

LVSIBVS IPSA SVIS GENERABAT SAEPE ET AMORE

DVLCE SIBI NATISQVE SVIS QVOS PVBE RELIQVIT

CASTOREA FRATRES SVB IMAGINE QVOS GENERAVIT

DIGNA QVIDEM FRVI PERPETVA DE LVCE BENIGNA

SET CELERAT QVO NOS FATA BENIGNA VOCANT

P[ublius] MATTIVS CHARITON CONIVGI B[ene] M[erenti] F[ecit]

Here in a respectable tomb lies Glyconis, free from care.

She was sweet in name and even sweeter in spirit.

She never strove for the frowning honors of life for herself,

but rather for the playful, pleasant honors—to steep in Bacchus

and to go through songs without elaboration, and soft garlands of flowers.

In her playful hours, she herself often used to create these with sweet love

both for herself and for her sons, whom she left at the time of manhood,

brothers whom she bore under the model of Castor [and Pollux].

She was indeed worthy to derive enjoyment from an endless, kindly life,

but she hurried to the place where the kindly Fates call us.

Publius Mattius Chariton set up [this monument] for his well-deserving wife (CIL 6.19055; second century CE).

The form of Chariton's name suggests that he was a freedman; his wife may also have been freed, although she is referred to without a nomen. This long and very unusual epitaph is actually a ten-line poem. The first nine lines are in dactylic hexameters, the meter of epic poetry. The tenth line is a dactylic pentameter, the second line of the elegiac couplet, a meter often used for love poetry. Despite the colloquial misspellings (set, nucquam, suabes), the poem has some sophisticated features. The name Glyconis is derived from the Greek word meaning “sweet,” and the whole poem is based on the association of this woman with all the soft, sweet, playful, pleasing things in life (well contrasted with tetricos, whose primary meaning is “frowning”). Glyconis has twin sons who resemble the divine twins Castor and Pollux. Many of the words in the poem also have erotic undertones (lascivos, lucibus) that sharply contrast with words such as honesto and honores. But the tone of the poem is as playful as Glyconis herself. There is no suggestion of censure here; Chariton (whose own Greek name means “grace, kindness”) is celebrating his fun-loving wife, not condemning her. The contrast in the use of benigna in the last two lines is striking; at first it refers to the kindly sort of life that Glyconis deserved, but its juxtaposition with the Fates who called her away too soon is bitterly ironic.